David Energy

The future of the electricity grid in America

This past weekend, I had a blast attending DERVOS 2024 in Brooklyn, an annual get together for the coolest nerds in the distributed energy space. As I get back into the renewable space, I couldn’t think of a better way to meet new people and learn from the best. After the event, I thought I’d do a small write up of David Energy, a startup poised to merge the capabilities of a retail electricity provider (REP) with software intelligence, whose CEO, James McGinniss, helped organize the conference in the first place.

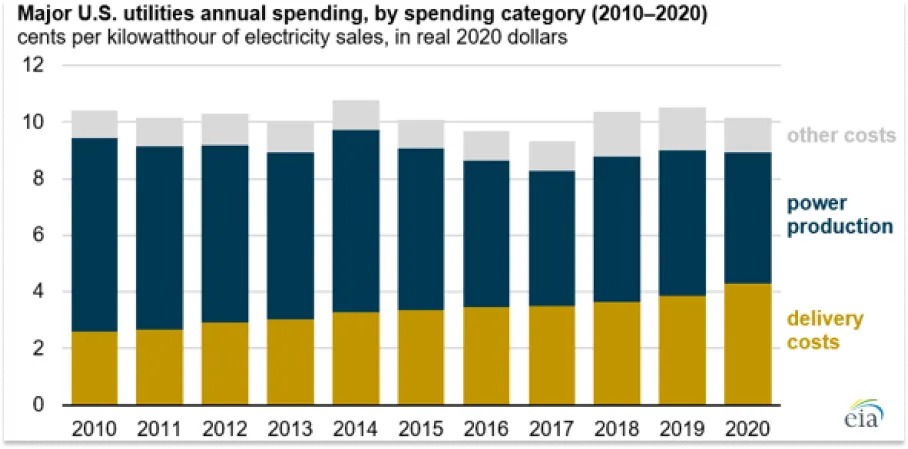

David fits into the broader picture of how I plan to tackle learning more about the electricity industry. To paraphrase Packy McCormick, electricity costs are made up of 3 legs - generation, delivery, and consumption, where generation is made up of sources such as nuclear, solar, and wind; consumption (demand) is the electrifying of traditional fossil use products uses such as cars, appliances, and heating; and finally, delivery, which is made up of two components:

Transmission - Long distance, high voltage transportation; the interstate highway of the grid

Distribution - Short distance, low voltage from substations to homes and businesses; the last mile of the electric grid

So to understand the renewable energy sector, it isn’t enough to know about the energy itself, but to also understand the underlying infrastructure - the grid - and the players that govern the actual delivery of energy from source to consumer.

And it’s this chart that’s linked in Packy’s excellent write up of Base Power, another REP, that got me thinking about David Energy in particular. Before I dive into what David does, I thought I’d talk about the problem it’s trying to solve.

Source: EIA

The Challenge at Hand

The problem is simply said but dazzlingly complex. With renewables continuing to make up a increasingly larger portion of the US’s energy consumption due to falling costs, and electricity demand is growing due to people adopting more EVs, electrical heating pumps, induction stoves etc, we’ve come to the energy industry’s version of Patagonia - jagged peaks descending into a brutish chasm of chaos.

Cerro Torre, the legendary peaks of the Patagonian Ice Field in Chile

Renewable energy is volatile; solar energy and wind power are intermittent, and thus don’t make sense as a baseload energy source. Solar, for instance, is at its highest supply (and cheapest price) in the middle of the day, when the sun is shining strongest; this supply quickly dries up at night when then sun goes down.

But because people use the most electricity at nighttime when they come home from work, a gap emerges; just when solar energy supply shutters down as night approaches, electricity demand increases as people turn on their TVs, showers, ovens, and charger their EVs.

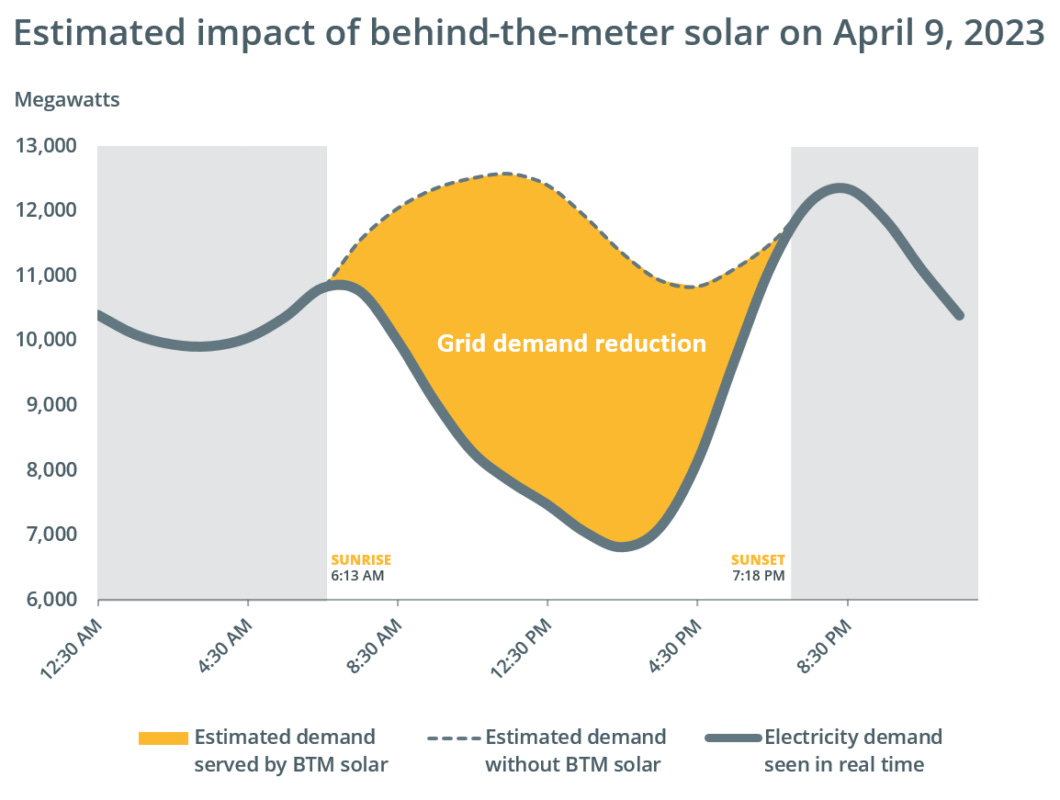

Figure 1: ISO

During the day, users who rely on behind the meter (BTM) solar - rooftop solar is a good example of this - don’t demand much electricity from the grid, as their needs are met by cheap and plentiful solar energy from their own households. Power plants are not ramped up during, given the lack of demand, which is represented in Figure 1’s grid demand reduction area. Instead, the solid gray line - “Electricity demand seen in real time” - highlights the actual demand, with a violent swing of 5,000 MWs from 2PM to 8PM.

Energy providers are forced to ramp up quickly to meet this demand, which causes several issues. As described by the U.S. Energy Information Administration:

The duck curve presents two challenges related to increasing solar energy adoption. The first challenge is grid stress. The extreme swing in demand for electricity from conventional power plants from midday to late evenings, when energy demand is still high but solar generation has dropped off, means that conventional power plants (such as natural gas-fired plants) must quickly ramp up electricity production to meet consumer demand. That rapid ramp up makes it more difficult for grid operators to match grid supply (the power they are generating) with grid demand in real time. In addition, if more solar power is produced than the grid can use, operators might have to curtail solar power to prevent overgeneration.

The other challenge is economic. The dynamics of the duck curve can challenge the traditional economics of dispatchable power plants because the factors contributing to the curve reduce the amount of time a conventional power plant operates, which results in reduced energy revenues. If the reduced revenues make the plants uneconomical to maintain, the plants may retire without a dispatchable replacement. Less dispatchable electricity makes it harder for grid managers to balance electricity supply and demand in a system with wide swings in net demand.

Clearly, there’s a core issue of supply with the introduction of intermittent renewables into the grid. The actual timing of renewable injection into the grid doesn’t match up cleanly with the demand timing, and it’s slowly breaking the grid, causing outages, and raising energy bills.

Introducing David Energy

Which brings me to David Energy - a startup based out of NYC, that can be best described as a software infused Retail Electricity Provider (REP).

Today, the energy market works like this: traditional REPs buy energy wholesale in markets from generators, and sell that to end users such as households in a one way process. They don’t own the underlying infrastructure such as wires that delivers the actual energy; the utility own that. Instead, REPs simply focus on buying the electricity in real time based on consumer demand, and have the utilities worry about the actual physical delivery.

Sometimes, utilities and REPs can be the same entity; other times, they can be separate. For instance, I live in the Hudson Valley, and Central Hudson is my utility, but I can shop for contracts with REPs listed on their website that are approved to operate within the areas covered under them.

REPs are powerful entities because they have real time market data from their consumers on when they need power; to solve the supply and demand imbalance in the grid, you need to become an REP to have this data. So like other REPs, David Energy buys power on markets, and sell them to consumers.

But David differentiates themselves from other REPs in one key way, made possible by one key technology - Distributed Energy Resources (DERs)

I’m not going to go on a wildly passionate spiel about DERs right now - smarter people like the DER Task Force that hosted DERVOS 2024 have a popular running podcast on DERs can explain it better, deeper, and sharper than me - but in short, these are technologies that are changing the general roles that consumers used to play in the electricity market.

Let me borrow some words from James McGinniss, the CEO of David Energy, about the true value of DERs:

On the demand side, DERs are changing how consumers act entirely. These are assets like rooftop solar, battery storage, smart thermostats, generators, and electric vehicles. DERs connect to the grid at the distribution level in a consumer’s house or building and produce power where it’s consumed. This allows users to respond dynamically to market signals with software in ways they never have before: they can sell solar back to the grid, turn batteries on and off when they like, or adjust their building’s HVAC system to lower their demand when prices are high. This means the grid is becoming more like a two way network, away from the old centralized model.

Source: Introducing David Energy

Consumers now play an active role, no longer passively at the mercy of REPs, in the energy markets, all because of an explosion of boundary pushing tech. And this is where the genius of David lies. To tackle the aforementioned supply and demand mismatch in today’s energy markets, David, through its software platform, is able to connect and control DERs devices in consumer’s homes, so while David’s REP arm is out there buying electricity, it can adjust demand up and down in each consumers homes to lower their energy usage during times of high prices.

Let’s run through an example to illustrate this, tying everything together in this post. Let’s say we’re a household that owns just a battery storage unit, and sign up with David Energy to save money. During the day, high generation output from solar floods the grid with cheap electricity, at a time when there is not much demand from households. Excess power from the grid is stored in your battery, at very little cost to you given the oversupply in the market. Then, when prices spike (usually at nighttime!) David’s software platform is able to leverage data from its REP arm to notify your battery to sell power back to the grid at a profit.

Source: Thunder Said Energy; you want to buy at hour 12, and sell at hour 20

This was my “a-ha!” moment when reading about David. Pretend if you’re a household with a battery but no access to David’s platform. As a singular household, you’re not going to get real-time market data, since you have no REP data to peruse. You could guess the best time to resell your battery power into the grid, and hence a profit, but David makes this more of an exact science, having an intimate understanding of minute to minute changes in the market, and the absolute best time to sell based on current demand and supply indicators.

This is the final value proposition that separates David from other REPs. Other REPs make money on their wholesale bought energy if you use more of it. They incur a certain cost of goods sold on the power they bought, and they only make a profit if they sell it a higher rate. And like any business, it becomes a Price * Quantity analysis. The more quantity of power they sell to consumers to use, the more money they make.

But David is different. Instead of a fluctuating, variable charge that REPs give to consumers at the end of each month based on their usage, David wants you to use less power. David charges a fixed, SAAS fee each month for access to their platforms - their offer is only profitable if customers spend less on both their new energy bill and David’s monthly fee versus their old energy bill. Going back to James’s post:

We make money by getting paid a subscription to our software platform that will handle all of a user’s DERs and energy buying. There’s no huge markup on the power we buy; we just want to keep users happy so we can keep collecting our fees. By relying on SaaS fees, we can cut fat out of contracts and introduce transparency into an opaque, commoditized process. Furthermore, while we’re out buying supply, we can adjust demand. We’ll have a hedging tool no other REP does, allowing us to create ever cheaper contracts.

Source: Introducing David Energy; emphasis added by author

This physical hedge concept is the flywheel that can potentially turn David into an energy superpower, and is the last thing I wanted to write before ending this section. Since David is facing two limitations here:

They won’t charge a high markup on the power they buy to offers lower prices to customers

They can’t buy energy during high price times at the rate other REPs do; otherwise, those costs will be passed on to customers or as losses to them

David must act differently. They employ a “physical hedge”, where they can adjust physical electron demand from consumers to buy power at the cheapest times, so they, as an REP, can procure energy at cheaper rates - an ability no other REP has.

Meanwhile, other REPs use financial hedges to hedge against price jumping, where they need to buy extra power in advance to match demand. This deteriorates margins, and most importantly, passed on higher costs to consumers.

The inverse of this is when David is able to use its physical hedge to lower costs for consumers, this delivers more customers to their doorsteps, leading to more physical hedges, lead to even more money saved, and so on and so forth. This is the flywheel that was promised.

Final Thoughts

This was a lot, and I’m sure I glossed over a few things. Energy is complex; the grid, even more so! But when I write about young startups like David Energy, I like to think in terms of an investment. Would I put money into this company if given the chance? On what criteria should I evaluate them on?

I’ve taken a note on this investing process from Julia DeWahl, who co-founded Antares, a nuclear startup looking to make energy abundant.

This isn’t a comprehensive mimic of her process, but some key questions I found useful when evaluating is:

Why is this the team to build a winning company in this space?

I’ve listened to James talk about his story in founding David, and it’s struck me that he really is an obsessive about his craft, who’s certainly passionate about the electrical grid while focusing more on the bigger picture of the industry as a storyteller (Check out his spiel on his skillset as a CEO here). Hearing him talk about power markets at DERVOS 2024 last week only swayed me more to the affirmative here.

How deep and specific is the customer pain / need?

I think a failing grid that can’t modernize is inherently and intuitively an incredibly deep problem for customers, ranging from outages to rising energy bills. The demand response programs that David is purporting to advance to make the grid more flexible is something I’ve seen come up again and again in literature I’ve read to get up to speed in this space

Saul Griffith’s “Electrify Everything” dedicates a whole section to the value of demand response programs, and whole matching supply to load demand will balance the grid (Section starts on PDF page 101)

Doomberg ran a skeptical article “No, Solar Isn’t Cheap” this year on why solar isn’t as cheap as everyone says it is (TLDR: Spot prices of solar don’t equate to delivery costs to customers because they don’t account for intermittency). One of it’s main critiques was that a proposed solution of shifting demand to match solar’s intermittent supply meant reconfiguring the entirety of society’s activities to the whims and wishes of solar and wind. I could simply be misreading the extent and breadth of this critique, but it seems that David is solving this issue with its REP+ software approach.

What’s the business model, and what are the advantages and risks of that model?

The risks of being an REP is that, at the end of the day, hedging can only take you so far, and there still remains risk that wholesale prices are so high and volatile, and that there isn’t enough DERs to smooth out the demand curve to match supply, that the marginal cost savings David does incur won’t make up for their monthly fee charged to customers. And if the flywheel of acquiring more customers makes their offering cheaper is true, the inverse of that is also a dangerous cliff to consider as well.

Why now?

Simply put, the rise of renewables being pushed by falling solar, battery and wind costs along with stringent goals set by governments means the grid will only get more unstable in the future, and the rising demand of electricity will only stress the grid more. A more volatile, more outage-prone grid will lead to a higher demand to DERs to keep households insulated from grid risk, which will only benefit David as the more households that have DERs, the more potential customers arise that fit within their value proposition. The falling costs/rising penetration of renewables and leaps in DER technology makes this the perfect time for a decentralized grid to exist, thus enabling a REP/Software model business to explode.

What do you have to believe for this grow into a huge business?

Growth of DERs will be critical. As mentioned in Saul Griffith’s book, David’s flywheel concept, and the breakdown above of the physical hedge, the bigger the pool of DERs available, the more the demand curve can be smoothed, and the cheaper their products can be. If no DERs exist, David Energy wouldn’t have the infrastructure to continue as a going concern. If everyone has DERs, David Energy will prevail over the incumbents. To become a huge business, the DER market needs to continue to grow; for what it’s worth, Wood Mackenzie projects the DER market to double from 2022-2027.