The Price is Wrong - Why Renewable Power's Growth is Lagging

Notes from Brett Christophers' powerhouse book

If you’re working to situate yourself into the climate space, there isn’t a better book to read than “The Price is Wrong”, a near 400 page book from Brett Christophers that slices through why current renewable growth lacks the momentum to meet climate goals. It offers a diagnosis on the problem, then a powerful solution, but to get the book up and running, Christophers starts off with table setting - he dives into the business of power, and explains why despite record renewable growth, we’re deeply off track to where we need to be.

Christophers’ thesis is compelling: profit, not prices, dictates the willingness of private market actors to push for renewable investment - falling costs do not necessarily indicate profitability. But it also doubles as an excellent guide of power markets and its complex mechanisms, which, after pouring through other books nonstop, I have to admit that no one has quite written sharper or more thoroughly on the subject than him. Below are my (paraphrased) notes on Christopher’s main thesis, and a real life case study to highlight his point.

I. The Thesis

Source: Flowcharts

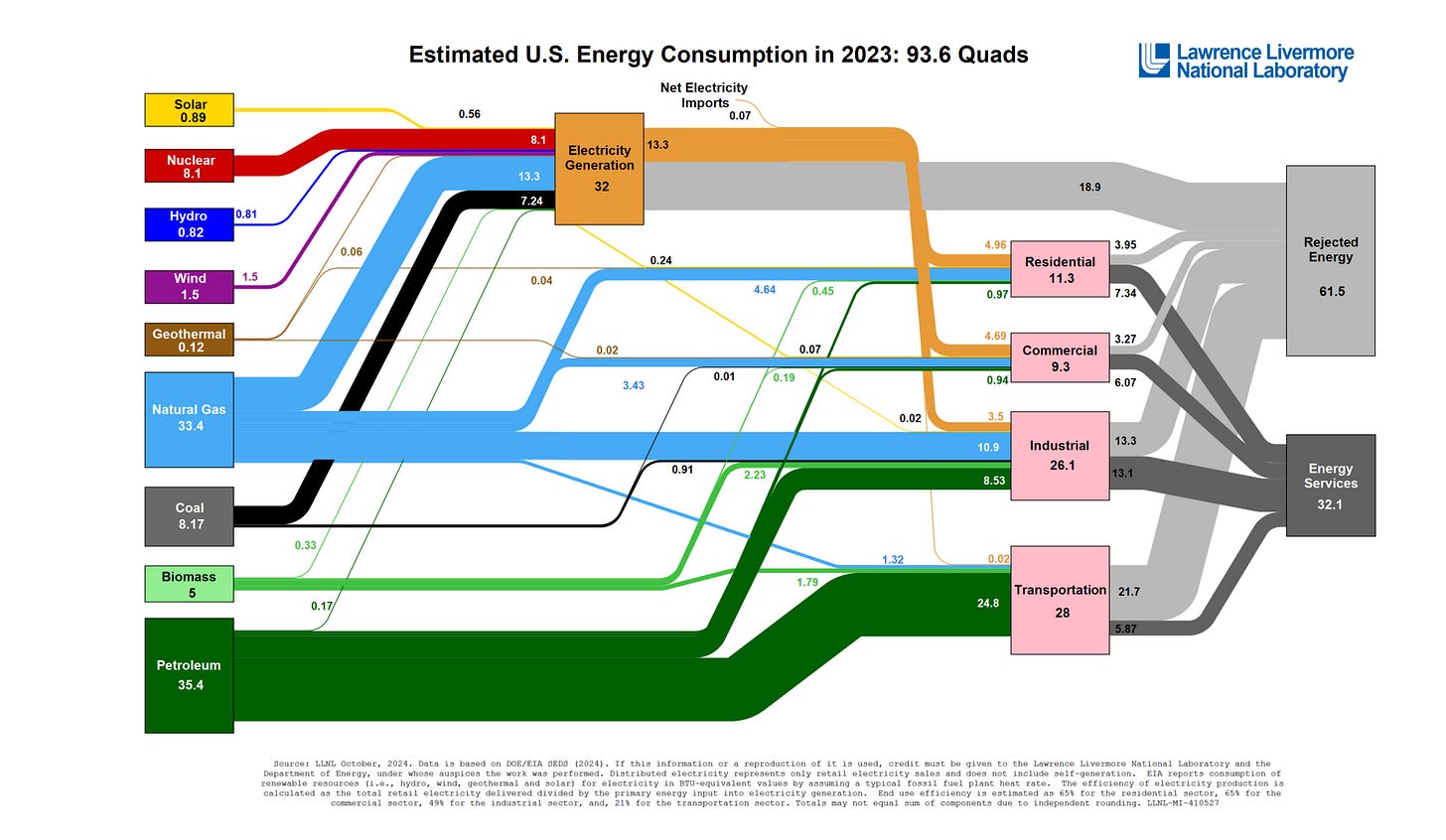

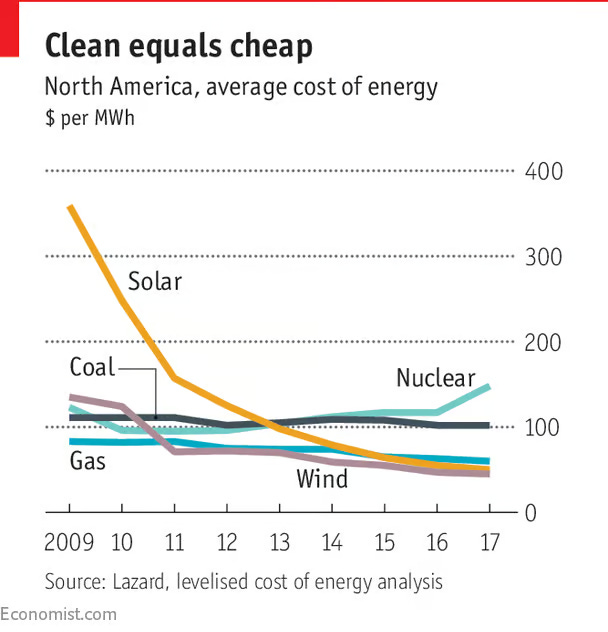

Electricity generation, which currently makes up ~35% of primary energy generation in the US (32 Quads / 93.4 Quads in Sankey diagram, above), has often been labeled as the most important battleground for decarbonizing the electric system - to shift production from fossil fuels (primarily coal and natural gas) to zero carbon sources such as solar and wind. However, due renewables being much more expensive, this has been considered to be a moot point - until recent history. Observe:

Source: Economist; see how Solar and Wind have blown past coal and gas based on costs

But Christophers argues that we’re looking at it all the wrong way. He notes:

“The better, more meaningful, yardstick is profit. This is what we should be focusing on. The main economic reason why the decarbonization of electricity is progressing so much slower than we need it to, I argue, is that most government worldwide have effectively outsourced responsibility for developing, owning, and operating solar and wind farms to profit-oriented private sector actors, and yet the profits that such actors expect to be able to earn from investment in these activities generally underwhelm. It is simply not a sufficiently attractive economic proposition.”

Source: “The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page xiii

With a focus on solar and wind, and limited to the commercial utility-scale sector (excluding the distributed generation business, which has different drivers) , Christophers makes his viewpoint clear: Capitalism is insufficient to push across the the massive scale of investment needed to meet climate goals by 2050. Despite blaring headlines crowing about renewable growth, something is amiss.

Put it this way, despite the impressive YoY growth of solar and wind since 2000 in the this space (Christophers has it around 25% in the past two decades; 32 TWh in 2000 to 3,435 TWh in 2022)1, because of rising global electricity consumption - especially in areas that are more carbon intensive - renewables have barely kept pace. Daniel Yergin, who wrote that ridiculously ambitious tome “The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil”, helped pen an article recently about this very same issue, noting:

“Yet 2024 was a record year in another regard, as well: the amount of energy derived from oil and coal also hit all-time highs. Over a longer period, the share of hydrocarbons in the global primary energy mix has hardly budged, from 85 percent in 1990 to about 80 percent today.”

Source: The Troubled Energy Transition

Which ever way you might want to measure, we’re falling short. To put it in absolute figures, a conservative figure from the IEA would necessitate 48,000 TWh from solar and wind by 20502, up from 3,400 TWh in 2022 - and by all accounts, this estimate might be conservative! To put it relatively, well:

“To meet the global goals, installed renewable capacity would have to grow from 3.9 terawatt (TW) today to 11.2 TW by 2030, requiring an additional 7.3 TW in less than six years. Yet, current national plans are projected to leave a global collective gap of 3.8 TW by 2030, falling short of the goal by 34%.”

Source: IRENA

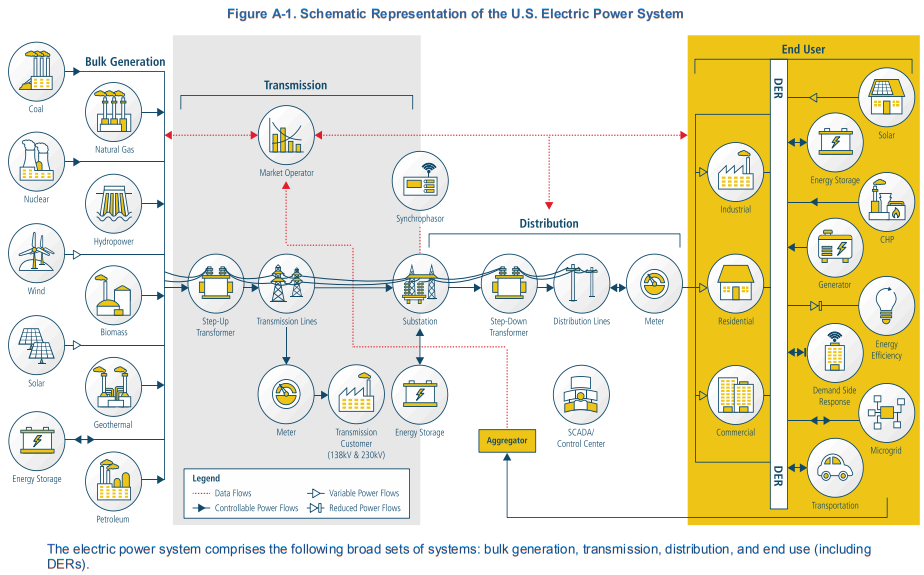

It’s important to note that what we really care about is the generation side of the business - they are the ones that bid their services to have their energy sources connected to the grid, which drives installed capacity. In terms of the value chain in the electric power markets, generators sit on the left side of the below chart, feeding their power into the grid to be transmitted, then distributed to end users.

So the way to think about this is that if generators don’t have sufficient profitability for their renewable investment, they simply won’t invest in renewable capacity! Which is logical - under capitalism, rational private actors only seek out profitable decisions. Christophers notes here a few couple drivers that, in general, stifle renewable electricity generation profitability:

Thanks to a low moat, intense competition in the generator side of the market naturally depress profits

Additionally, competition limits the ability of generating companies to capture cost reduction of renewable energy sources. This is a classic economic case study, where intense competition triggers a price-cutting war amongst sellers, and the value of reduced price of electricity is passed down the value chain instead.

“But the crucial point is clearly this: the particular industry constituency that the world is relying on to actually, physically, make the switch to renewables - that is, generating companies, those that produce our electricity and sometimes also, in the process, produce greenhouse gas emissions - is seemingly not the industry constituency that would stand most to gain economically from that switch”

Source: “The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 147

The profitability of renewable investments are not competing against the profitability of fossil fuel plants. Instead, they’re competing against simply doing nothing

Thus, what matters here is the hurdle rate the investment needs to clear. If a firm has a 10% IRR as a hurdle rate, investments that fall below are a no pass. There are cases where renewable investments are more profitable now than fossil fuel investments, but that is not sufficient to garner monetary investment for the project to proceed to NTP3 ( money being in the form of CapEx for construction, permitting etc)

So his point can’t be made clearer than this - In a free market, you can stop people from doing profitable things, but you can’t make them do unprofitable things.

II. The Wild West

Profitability drives investments. Great. That makes sense to anyone who’s been in the business of business. But this point lacks the texture inscribed in the electricity markets, which is something I became all to aware of after reading this book.

About halfway through “The Price is Wrong”, Christophers pens an Agatha Christie novella in the chapter “The Wild West”. He writes:

“In 2018, something remarkable happened to the UK’s onshore wind industry. Having grown to nearly 2.7 GW in 2017 from below 500 MW a decade earlier, annual installations of new capacity, in the words of the trade association RenewableUK, suddenly ‘plummeted’. Less than 600 MW of new capacity, comprising just 263 turbines distributed across fifty-four sites, were brought to market during the year, representing a year-on-year decline of approximately 80 per cent. It was the lowest level of annual installation of new onshore wind generating capacity the country had seen since 2011. What, then, had happened? What - or who - was to blame for this historic failure?”

Source: “The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 163

He quickly rules out suddenly rising equipment costs (think turbines, for instance) or permitting restrictions that can put projects in a queue that go around the block. He highlights wholesale electricity prices4 were also healthy (sitting prettily in the 50 pounds/MWh to 70 pounds/MWh).

Instead, he notes that the UK’s electricity market is distinctively marketized; since the early 1990’s, the UK electricity sector has undergone a neo-liberal driven agenda that has shifted control from the state to private actors; notably, generators, which are the actors that determine whether renewable energy capacity is hooked up to the grid, were unbundled from a previously vertically integrated value chain and thrown into a wolves eat wolves market.

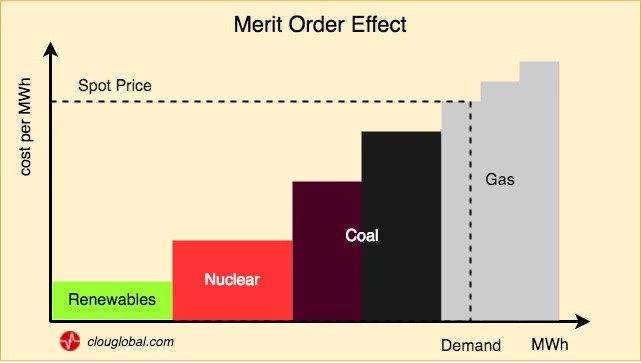

In addition, the way generators bid into the market in UK is determined by merit order dispatch. This means:

Generators submit bids to the system operator (National Grid ESO for the UK), specifying quantity of electricity they expect to produce, for what time period, and at what price they’re willing to sell it.

The operators match supply and demand by stacking each generators’ bids from lowest to highest cost until the cumulative supply matches the projected demand for that time period. This matching of supply and demand is seen below.

The price paid to all generators is not the price they submitted - rather, a single price it paid to all generators. This price - which can be referred to as the wholesale, spot or merchant price - is the price requested by the most expensive bid that was accepted by the system operator. In the below graph, the price is set by the gas.

Prices bid by each generator reflect their marginal costs; generators won’t bid until the pricing clears their marginal cost to produce a unit of electricity. There is an exception, however. Renewables have a marginal cost of zero, given the lack of fuel costs, so their bid price would be zero. However, their bids reflect something else: amortizing the upfront capital investment needed to build the generator in the first place

Source: CLOU Global

What does this all produce? Price volatility.

Here’s what happens. Merit order dispatch prices electricity at the final unit to necessary to balance supply and demand. And because energy sources have different costs profiles (gas is usually pricier than renewables), but share similar costs within energy sources (renewables are generally priced the same), the cheapest bids comes one energy source (renewables), and the priciest ones come from another (peaker gas plants).

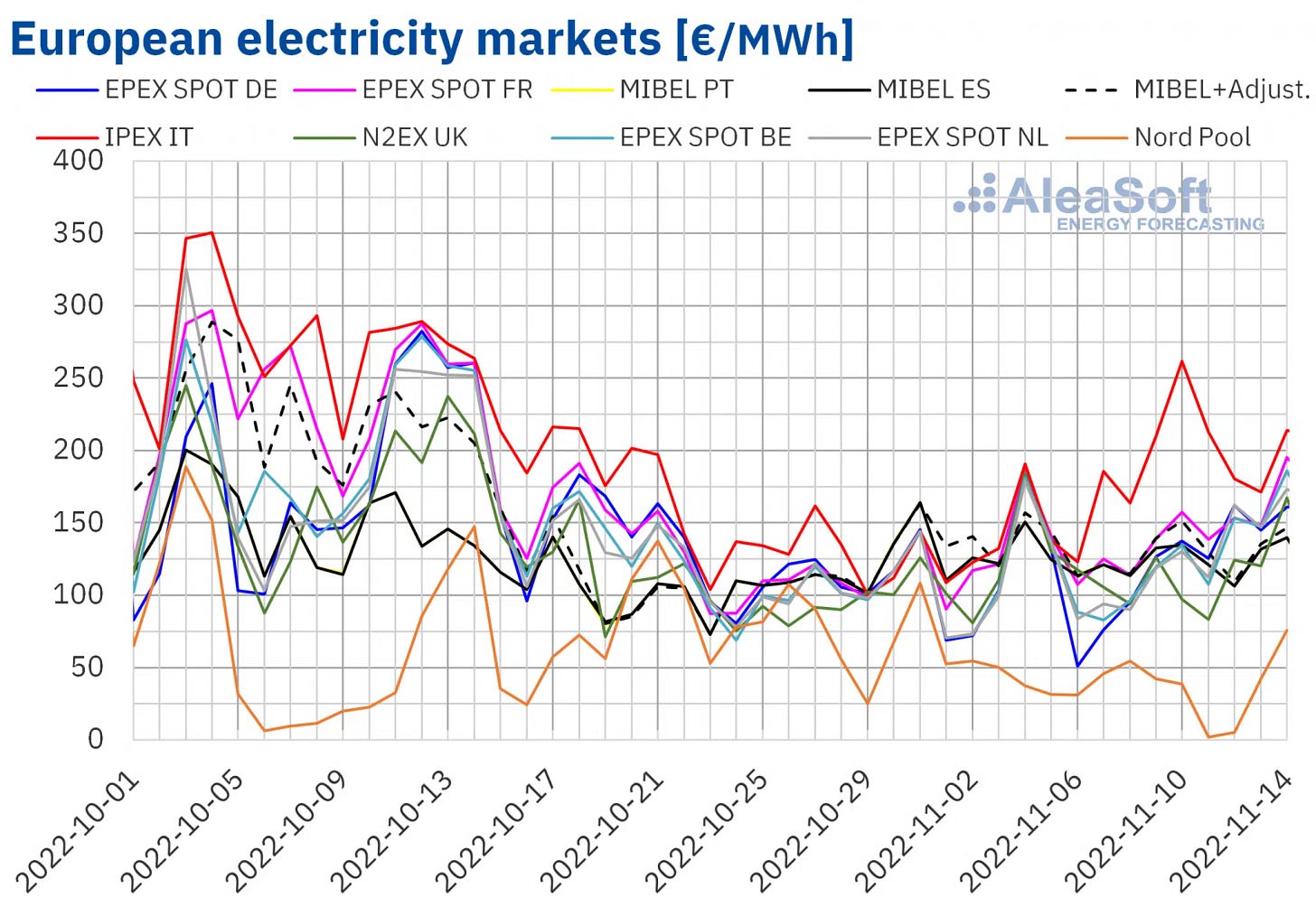

So imagine if the sun is shining, the wind is blowing - renewable generation is high, and can cover the entire demand curve. Thus, electricity price is set by the bid price of renewables. But if there is very little renewable generation, and electricity demand is high, expensive gas prices can set the price for the entire market, leading to volatile charts like the one below.

Source: AleaSoft

Christophers sums this up succinctly:

“How large was the concomitant day-on-day change in the SE3 electricity price? Nearly 1,000 per cent! On 21 August, the day-ahead price was €38 per MWh, on 22 August, it was €372. Can there be any other product, anywhere in the world, subject to such volatile price movement?”

Source: “The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 172

Another problem arises as well. Beyond volatility caused by generation switching setting the market price, there’s also a shift in each generators’ costs, changing their bid prices.

This is an issue for fossil fuel based generators. Conventional generating plants rely on commodities (fuel) to operate, which are volatile themselves. In the UK electricity market, gas fired plants set the market price of electricity 80% of the time, despite the fact that they only accounted for ~40% of the country’s electric supply. So when natural gas prices roses, those raised the marginal costs of natural gas generators, raising the bid price of those same generators, raising the electricity price for all consumers in the UK.

So back to renewables. Price volatility gives the bankers who often finance renewable projects cold feed in investing in them. This makes sense. Price is the P in the P*Q calculation to determine revenue for each project; if revenue isn’t stable, cash flow isn’t stable, and if cash flow isn’t stable, its fair to wonder if projects, which are often backed by debt through project financing5, are able to repay their annual fixed debt payments. Projects that are at the mercy of these volatile wholesale prices are derisively called merchant projects.

Banks are willing to finance these projects, sure, but with greater risk comes a need for greater return. The IRR threshold of these projects jump, raising the standard needed to meet financing. Oftentimes, these projects simply can’t make the leap. Per Christophers, banks will charge 3 times more for merchant projects, and an interest rate of 5% becomes 15%.

There’s another funny piece in the chapter that explains a final nail in the coffin for many renewable projects vs gas projects. Renewable generators lack an inherent hedge that gas plants have. It goes like this:

Operating renewable plants have to pay fixed costs to service debt - their operating costs are fixed, no matter the electricity price. So if electricity prices fall, revenues fall, but costs stay the same —> reduced profitability

Electricity prices often fall in tandem with natural gas commodity prices in the UK. This is because gas plants often set the market clearing price, so when natural gas prices fall (their operating costs!), their bids can decline as well to reflect those lower costs, leading to a lower market clearing price. So while electricity prices might fall for gas plants, their operating costs generally do as well. In essence, their profitability remains the same.

All these factors contribute to the fact that governments often have to subsidize renewable projects through price stability mechanisms. Policies such as feed in tariffs (FIT) or Contract for Difference (CFD) work by providing renewable generators a fixed price point over a certain period of time, guaranteeing the bankability of their projects. Without them, their security steps on much shakier ground.

Which brings me back to the collapse of the installation of UK onshore wind projects in 2018. It wasn’t caused by technological issues, or poor permitting outcomes. Instead:

The cause was a policy shift. The one government support scheme for which new UK onshore wind projects were still eligible in 2017 - the Renewable Obligation scheme - was closed that year. Meanwhile, such projects were barred from competing in the new CfD scheme. Denied, thus, any kind of ‘market stabilisation mechanism’, onshore wind, as Henry Evans observed, was abruptly subjected to ‘the volatility of the market’.

The reaction of the relevant stakeholders was entirely predictable: they exited new development en masse. Keith Anderson, the then chief executive of Scottish Power, one of the UK’s leading developers and operators to that point of onshore wind farms, expressed the private sector’s standpoint best, speaking bluntly - but not less eloquently for that - for the industry and its backers as a whole. ‘If you think I’m building a £2.5bn wind farm at merchant risk on wholesale power prices’, Anderson said, ‘then you’re bonkers’.”

Source: “The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 188

“The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 15

“The Price is Wrong” by Brett Christophers. Page 30

NTP = Notice to Proceed, which signals the start of construction on a project

These are prices found in wholesale markets, as opposed to retail markets, which is electricity sold directly to end consumers. In the wholesale markets, intermediaries such as regulated utilities and electricity providers buy them. A higher price is good for generators! This generally fattens up their top line: revenue.

Project financing is done through debt because debt is cheap, and raises the IRR of equity sponsors. Here is a good primer on project finance